Luminarts Fellows By Year

2016 Fellows

Page Currently Under construction.

2015 Fellows

Kayla Anderson

Kayla Anderson is an interdisciplinary artist and writer. Using a playful approach to methods of excavation, her work engages with cultural artifacts of the past in order to propose parallel worlds. Through intricate installations involving video, sculpture, and found objects, she challenges perceived boundaries between subject, object, and image.

She received a BFA with emphasis in Film, Video, and New Media and Fiber & Material Studies and a BA in Visual and Critical Studies from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago with a thesis on the intersections of object-oriented ontology and media art. Her work has been exhibited in galleries and museums throughout the US and Southeast Asia.

Her writing has been published by Leonardo Journal of MIT Press and the Royal College of Art, and presented at SIGGRAPH 2014, SIGGRAPH 2015 and the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center at the UCSB. In addition to her art practice, she has curated several exhibitions focusing on film, video, and new media art, including Freeze Frame: Artists Books and the Moving Image at the Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection, and [History] Under Construction at Gallery X, Chicago, IL. She currently holds the position of Manager of Library Special Collections at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she curates exhibitions, lectures, and mentors students in the history, theory, and creation of artists’ publications. In her spare time, she organizes a monthly critique group for female media makers called Media Grrrl.

To learn more about Kayla visit Kaylanderson.com

- Beaming Baudrillard No. 073

- Beaming Baudrillard No. 086

Jeffrey Michael Austin

Jeffrey Michael Austin is an interdisciplinary artist, musician and educator based in Chicago. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including such venues as Le Carreau de Cergy (Paris), Chicago Artists Coalition,Kunstenfestival Watou (Belgium), The University of North Texas Art Galleries, Lehr Zeitgenössische Kunst (Berlin), The Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Fondation Vasarely (Aix-en-Provence), The SUB-MISSION (Chicago), Terrain Exhibitions (Oak Park), and Manifold (Chicago) in conjunction with the ACRE Artist Residency. Other residencies include the Ed Paschke Art Center Chicago, the Center Program at the Hyde Park Art Center, the BOLT Residency with the Chicago Artists Coalition, and Chicago Artists Month: CONSTRUCT.

Austin received his BFA from The School of The Art Institute of Chicago and currently works as Deputy Director of The Chicago Perch and as a Teaching Artist with Marwen. To learn more about Jeffrey visit Jeffreymichaelaustin.com.

- I’m Not Worried About You

- You Think Too Much

Thomas Caminito

Thomas Caminito is a Luminarts Fellow in Jazz. Thomas Caminito is a Chicago-based jazz saxophonist specializing in contemporary improvisational music. After beginning his saxophone studies in middle school, he continued onward to obtain a bachelor’s degree in jazz composition from the highly-esteemed Berklee College of Music in Boston. While at Berklee, he studied jazz performance and composition under the tutelage of numerous prolific musicians and educators including George Garzone, Greg Osby, Ayn Inserto, Hal Crook, Dave Santoro, Scott Free, and Terri Lyne Carrington. Thomas is currently an active performer in the Chicago area pursuing a Master of Music degree at the DePaul University School of Music.

Daniel Camponovo

Daniel Camponovo is an East Coast ex-pat writer, linguist and educator living in Oak Park, Illinois. He is currently

pursuing his MFA in Creative Writing from Columbia College Chicago, where he is at work on his first novel. For the 2014-15 school year, he worked as a Teaching Artist for Storycatchers Theatre, a youth development arts organization serving marginalized Chicago students. He was born in the Naval Hospital outside Washington, D.C., lived 100 miles outside Philadelphia for seventeen years and has spent the past eight years in or around Chicago. He considers these three cities to be home. A student of linguistics before a student of writing, he is primarily interested in manipulating the structure and the grammars of language to most accurately convey the message, whatever it may be, in addition to exploring the manners through which the artist can alter or subvert the message via changes in the medium. His work is heavily inspired by family history, although his novel about a segregated neighborhood in 1950s Atlanta is not, and he has long been interested in investigating the layers of memory and cognition and the forces through which these layers become stripped away. He enjoys reading stories about people who are unlike him and places that are unlike his home, and he does his best to accurately represent them in his work. He is a staunch opponent of the serial comma, though he stopped enjoying debates about the subject during his post-graduate years.

Before the Rain (Excerpt)

C-H-E-E-R-I-O-S, I spelled. My fingers flicked hurriedly through the air. Luz nodded and I grabbed the box from the shelf. A woman nudged past me to grab her box of Cheerios and a man and his toddler wrestled over whether a Captain Crunch could come home with them. The din of motion and bustling energy in the store hurt my ears.

“What else do we need?” I signed to Luz. I had to wave to wrench her attention away from the box of strawberry oatmeal in her hands. She set the box back on the shelf.

“Things that won’t rot without power,” she said. “Cereal, bagels, fruit.”

“Oatmeal,” I said, nodding toward the box. “Throw it in the cart.”

She looked at my hands, then toward the box on the shelf before looking back to me. Her weight shifted between her legs, and her fingers twitched by her sides, as they did whenever she tried to figure out how to word something. She looked like a puppy that needed to pee.

“We ate this most mornings,” she finally said. Her body faced me but she looked to the oatmeal as she signed. “I made it for us.” When she finished, her hands hung in the air in front of her chest for a moment like a boxer’s before grabbing the box again.

“Forget it, then,” I said. “Let’s go.” I pushed our cart farther down the aisle, but she remained where I had left her, turning the box over in her hands. She studied the box as if rediscovering it — how much the oatmeal weighed, how she could feel the contents shifting inside, how the edges of the carton creased into sharp, folded corners. To get her attention I had to do a half-jumping-jack from the far end of the aisle.

“I’m not buying that,” I said. I exaggerated my movements and tried to silently enunciate across the distance. I felt very far away from her, and just before I begged her to come closer, she came. She strode down the aisle and placed the box in our cart, next to the bottle of rum and on top of the leeks. “I liked it,” she said simply. “I ate it too.” The oatmeal met our requirements for storm food — nutritious, spoil-proof, needed only a gas burner. “We need ice,” Luz said, and turned toward the freezers. Her hands jerked in the air as if they had turned into animal’s claws, or perhaps as if they had touched a hot stove. I couldn’t decide which looked more accurate.

When I had first seen the job listed in the catalog, I wondered why a women’s shelter would need an interpreter. I asked my interviewer this question, and she answered simply that the shelter needed people with as many skills as possible to cover all demographics, which I considered at the time to be a vague answer but have since come to appreciate in its ubiquity. The interviewer had asked how my vocabulary was, and I told her it was strong, which it was, and she asked me to show her. She handed me a manila envelope with a case file inside; the woman’s name had been whited out, but her date of birth and her measurements and what she was wearing the night she arrived, it was all there, enough that I could have painted a rough picture of her in my head. I saw her as having freckles, and a ponytail pulled through a baseball cap. I don’t know why I saw her that way, but I did. She looked like me, I guess is what I’m trying to say. It was strange to see what could have been a version of myself written in the sparse details of a medical file, but I saw myself in the height and weight measurements and the hair color, even those details which weren’t mine. The woman was even younger than I was when she was admitted to the shelter. I was 23 years old then.

The job interviewer asked me to sign the orderly’s notes at the bottom of the medical file, but I didn’t know how to begin. I didn’t know the sign for “stab.” I didn’t know “laceration” or “wound.” I knew “blood,” and I knew the various articles of clothing that the blood had soaked, but I didn’t know “stitches” or “painkillers” or any of the words that might have helped her heal. In my jilting, stuttering hands, she was frozen in her suffering, waiting for any language that might begin to make sense of what had happened to her. I lowered my hands back onto the table separating us. They suddenly felt very useless. The date on the file was six years old, and I realized the time for learning what had happened to this woman was past. I needed to believe she was happy now. “I shouldn’t have come here,” I told the interviewer. “I don’t know the words.”

“You’ll learn the words,” she said, passing me an employee contract and a pen.

Justin Copeland

Justin Copeland is a Luminarts Fellow in Jazz. Justin is a trumpet player, pianist, educator and composer. Justin has been performing extensively as a professional musician for over a decade all over the United States, and currently resides in the Chicago area. Justin completed a B.A. in music performance at California State University, Fresno (Fresno State) in 2011, and subsequently a Masters in Music Degree at Northwestern University in June of 2013.

Throughout the recent years, he has had the privilege of performing with and learning from world-class musicians inside and outside of Northwestern, like saxophonist, composer and educator Victor Goines, trumpeter, educator and counselor Dr. Michael Caldwell, trumpeter and educator Brad Mason, saxophonist, composer/arranger, and educator Christopher Madsen, saxophonist and educator Sherman Irby, trombonist Elliot Mason, drummer, composer/arranger and educator Rich Derosa, legendary bassist and educator Rufus Reid, legendary trombonist Curtis Fuller, world-renown jazz educator David Baker, and legendary saxophonist and educator Nathan Davis. Currently, Justin is pursuing a Doctorate of Musical Arts in Jazz Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Justin has also had the privilege to perform at some of the most premier houses of music, like new Orleans’ Premier Jazz Club, Snug Harbor, the Main Stage at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, the Chicago jazz festival, the House of Blues Chicago, Cliff Bell’s in Detroit, Merriman’s Playhouse in Southbend, in, Dizzy’s Club Coca Cola at Jazz at Lincoln center in New York City, and many more.

To learn more about Justin visit Justincopelandmusic.com.

Emma Dayhuff

Emma Dayhuff is a Luminarts Fellow in Jazz. Brooklyn based bassist, composer, and vocalist Emma Dayhuff was spurred to pursue the bass after being told she was too small to play the instrument, and was later inspired to study jazz after seeing Joey DeFrancesco perform in her hometown of Bozeman, Montana. In 2005, she was awarded the Dean’s scholarship to attend the Oberlin Conservatory of Music. Her mentors have included Peter Dominguez, Eddie Gomez, Vincent Davis, and Gerald Cannon. After graduating from Oberlin, she moved to Chicago where she was immersed in the city’s eclectic music scene initially as the recording engineer for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, then as a bassist. She recently performed at the 2015 Chicago Jazz Festival with “Generations” led by keyboardist, composer, and longtime Miles Davis collaborator Robert Irving III. She has also recorded and shared the stage with Grammy-nominated singer songwriter Matthew Santos, Rajiv Halim, Kahil El Zabar, Jumaane Taylor, Larry Brown Jr., Jimmy Chamberlain, and Don Stiernberg among many others.

To learn more about Emma visit Emmadayhuff.com.

RS Deeren

RS Deeren is a rural Michigan writer currently living in Chicago. “Home” for him, however, is the Thumb Region of Michigan; a three-county peninsula jutting out from the state’s Lower Peninsula, a palimpsest of geographic dead-ends. This area is what influences his writing and the characters in his fiction live lives with spinning tires, pressing the gas pedal harder but only succeeding in digging into the ground deeper.

His fiction has appeared in BartlebySnopes, The Corvus Review, Cardinal Sins, Botticelli Literary and Art Magazine, and elsewhere. His essay, “Chicago as a Conversation,” recently came out in the Chicago Center for Literature and Photography’s anthology, The View from Here. His short story, “Apes Moi le Deluge,” won the 2012 Tyner Award for Writing Excellence. Before moving to Chicago to attend Columbia College Chicago, where he is an MFA candidate in fiction, he worked around the Thumb as a short order cook, a substitute history teacher, a landscaper, a lumberjack, and a banker. He is currently working on a collection of short stories about Michigan’s working poor and a novel about rural male identity in the 21st century and how life on parole influences that identity. In an attempt to keep the ongoing tradition of putting his family at ease about his career, he would like to state for the record that none of the characters he’s created have been, nor ever will be, them. The only caveat to this is “Scott’s River,” but, he says, who wouldn’t want a river named after them?

To learn more about RS visit RSdeeren.com.

Lily Dithrich

Lily Dithrich is a Chicago based sculptor from Oakland, CA. She received her Bachelors of Arts in Studio Art with high honors from Oberlin College in 2013. Since graduation, she has been living and working in Chicago and has participated in a number of residencies and group shows. Most recently, she was awarded a fellowship to participate in the Anderson Ranch Arts Center fall Artists in Residency Program in Snowmass, CO. Additional residencies include the Ed Paschke Art Center, the Center Program at the Hyde Park Arts Center, Chicago Artists Month: CONSTRUCT, the Chicago Artists Coalition’s HATCH program, and she was featured in the exhibition, Suddenly Plastic, at the Chicago Artists Coalition.

To learn more about Lily visit Lilydithrich.com.

- Sitting Together

- Catch

Jessie Donner

Jesse Donner, tenor, is rapidly emerging on the operatic and concert stage with a voice that is “vibrant” (Chicago Classical Review), “fresh and juicy” (Chicago Tribune). In the 2015-2016 season, Donner will return to the Lyric Opera of Chicago as a second year Ryan Opera Center member in the roles of Abdallo (Nabucco), Kellner (Der Rosenkavalier) and covering the lead tenor roles, General Alfredo, in the world premiere of Bel Canto, Ismaele in Nabucco and the Drum Major in Wozzeck. In addition he will be appearing as a featured solo artist in Beyond the Aria with soprano Christine Brewer.

The 2014-2015 season brought Donner to Chicago for his debut with the Lyric Opera in the roles of Diener (Capriccio), Walther (Tannhäuser) and covering Walter (The Passenger). For his performance in Tannhäuser, Opera News remarked that “Jesse Donner fielded a notable Walther, who could be heard pealing above the ensembles.” On the concert stage, he debuted with Chicago’s Civic Orchestra in Poulenc’s Les mamelles de Tirésias and returned later in their season as tenor soloist in Mozart’s Great Mass in C minor. Donner also appeared this season with the Adrian Symphony as tenor soloist in Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9.

The 2013-2014 season held role and company debuts for the newly minted tenor. Donner sang Pinkerton (Madama Butterfly) with Opera in the Ozarks, Bacchus (Ariadne auf Naxos) with University of Michigan and as tenor soloist with the UMS Choral Society in Verdi’s Missa di Requiem, the Toledo Symphony in an evening of Christmas Favorites, and the Adrian Symphony in Handel’s Messiah.

The Des Moines native won the 2015 Luminarts Fellowship and the Bel Canto grand prize, received the 2014 George Shirley Award for Opera Performance, a special encouragement award from the 2014 Metropolitan Opera National Council Regional Auditions, and first place in the 2012 Michigan Friends of Opera Competition. Donner recently completed graduate and post-graduate studies at the University of Michigan. He previously received a bachelor of music degree from Iowa State University.

Daniel Glynn

Daniel Glynn was recently appointed Second Oboe of the Rockford Symphony in June of 2015. From 2012 to 2014, Daniel was the acting Second Oboe of the Sarasota Orchestra. Prior to this, he was the permanent Solo English Horn of the Sarasota Opera Orchestra under the baton of Maestro Victor Di Renzi. Daniel has also been a full-time member of both the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, as well as The New World Symphony. While a member of the Civic Orchestra, Daniel was featured as a soloist with members of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante.

Daniel received The Mericos Foundation Full Fellowship to attend the Music Academy of the West, as well as the Bowers Noyce Oboe Fellowship to attend the Aspen Music Festival. As the recipient of the Garwood Welch Scholarship, in addition to a generous Eckstein Grant, Daniel earned a Bachelor of Music, Arts Administration minor, and a Master of Music from Northwestern University. He was also the first oboist to receive the coveted Professional Studies Certificate from The Colburn School in Los Angeles, CA.

Carley Gomez

Carley Gomez has a BA in Creative Writing and English from the University of Arizona. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. While earning her MFA, she taught English and was a teaching assistant for multiple creative writing classes. Her collaborative artists’ book, “Playing House”, was shown at her 2015 MFA thesis exhibition, and is in the Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection. Her nonfiction work has appeared in the Chicago Literary Map. Her poetry and photography has appeared in Persona Magazine. Carley participated as a ULC Library Writer in Residence in spring of 2016, and is currently working on her Ph. D.

In Her Absence, by Carly Gomez

In the fall of 1966, my mother disappeared. I was ten years old and I thought that it was some violent trick a magician might do with a saw and a box. I was at the age when I still believed in magic, and that I was capable of performing it. When I was younger, my grandma used to sit with me on her lap and tell my mother who sat across the table sipping tea, that we Gilden women had to listen to intuition. I was certain for years that ‘Intuition’ was our family’s guardian angel who would tell me other people’s secrets or help me see the future.

At night, I would tell my three younger sisters who slept in the same room with me, that it was time for our special ‘ritual’ (another word Grandma used a lot). I’d make them get up—even Diana who was only five when we started—and stand around me in a triangle. We’d cover ourselves with a cherry blossom pink sheet and my sisters would pretend to hold candles while I whispered gibberish and contorted my body with a flexibility that I’d lose before puberty.

Eight-year-old Katy would watch with wide, green eyes, her awe so apparent that I’d always make extra predictions about what would happen to her in school the next day. They weren’t usually nice, but sometimes they were right. “A boy will try to peek up your skirt on the stairs!” or “You’ll get macaroni and cheese on your shirt during lunch.” And then I’d shudder and convulse on the ground. Leanne, who was only eleven months younger than Katy, always dropped her pretend candle and made faces at Diana.

The night that our mother disappeared, we had long since finished our ritual when I woke up to the sound of a crash. Shattering dishes, the everyday ones with lavender flowers wrapped around the edges, came to mind. I listened, waiting for my sisters to wake up, but their breathing stayed heavy. My father’s muffled voice travelled through the wall, but in wordless sounds. I sat up, combing my thin, blonde hair out of my eyes, and looked around in the darkness. For a few seconds, I could see nothing, but then in the direction of the doorway, a thin ribbon of light traveled up the wall. I blinked a few times, trying to see into the shine and finally I found my mother’s green eyes, widened with fear.

“Are they still asleep?” my father asked from behind her.

She mouthed something to me, but I could barely see her lips opening and closing. Then, the glimmer of her eyes disappeared and gave way to the shadowed contours of her face as she turned to my father. “Yes, they’re asleep,” she whispered. My mother gently closed the door behind her.

I stayed awake in bed for a while, picturing my mother’s terrified eyes, wondering what had broken. I imagined a teacup with a handle missing, a bowl with a chipped rim, a plate in pieces. After some time, I grew tired, and fell asleep. When I woke, my mother was gone.

_

In the morning, I asked my father where she was as I stirred oatmeal in a pot on the stovetop. I wore an apron that matched my mother’s. She had made them in pieces when I was five, searching for patches of fabric when we could afford it. The trim was a cream lace, the ties were blue, and the pockets were beige.

She was onto Diana’s apron now, but it wasn’t finished yet. The pieces of fabric were bigger and more detailed, the trim more intentional. She sewed less frequently though, stopping to cup a glass full of iced scotch. She said that her fingers ached from the needle and that the glass was soothing, but it only took her a few moments to finish her drink.

It was seven in the morning when I asked my father where she was. He was already dressed, his collar crisp, his black shoes reflecting the pattern of linoleum squares on the floor. He looked over the pot and inhaled.

“Don’t forget the brown sugar,” he said.

It felt strange to put on my apron and bring water to a boil when my mother didn’t appear in the kitchen. My father called me to make breakfast and there was no arguing with him, but I wanted to resist. There was still breakfast, still a routine. Missing her so immediately should not have been the only evidence of her absence, there needed to be a disruption. There needed to be smoke and a bang. We had to fall into chaos. But we didn’t. I asked my father again where she was. I knew that I might regret asking the question, but I figured I had to be at school soon anyway and he didn’t like interrupting our schedule with discipline.

He told me that she was at the doctor’s office. I nodded and he stood there watching me as I poured brown sugar onto the steaming oats. I pulled out the bowls from the cabinet and counted three. One was missing.

_

My mother was gone for three days, but I knew better than to ask my father where she was again. After school in the afternoons, Leanne and Katy would stare at the door and Diana would just stare at me. Her gaze made me uneasy, like I was expected to pull a coat aside in the closet and reveal our mother. It made me feel guilty somehow.

I got them to school everyday while our mother was gone. Our father had never driven us to school before and he didn’t start then. Every morning after breakfast, I brushed Diana and Katy’s hair, and I braided Leanne’s hair. We’d leave to school after I made sure their shirts were tucked in and their white shoes were wiped clean of dirt.

The first day we walked past the row houses with yellow awnings and pink flamingos in the yards of the houses our mother had told us to avoid, I was terrified. I thought for sure that someone would find out that we were motherless. It didn’t matter that our mother had only disappeared that morning, I thought that her immediate absence was something noticeable. Our father didn’t seem to be an acceptable substitute. He was the obstacle that we walked around in our living room and he spoke in sayings that sounded like they came out of fortune cookies. He said he was shaping us for adulthood. He talked about work ethic and how he bought his first car by selling eggs from his three hens.

After the yards with flamingos, we passed small houses with patches of grass that went limp in the heat, and we passed old men who sat on their porches skimming newspapers until we neared them. Cars filled the neighborhood streets as we got closer to our school, but the morning still felt quiet.

“Is our mother dead?” Diana asked. Our mother had taken us to school every single morning before this one, so Diana knew that there were questions worth asking. Death was the simplest of them, even if it made the least sense. As the youngest of us, she’d had no brushes with mortality yet; she knew the word from the fairytales I read to her at bedtime.

“She’s not dead,” I said. I was resigned to answering even though I knew that Diana didn’t know what the word meant. I crouched down in front of her and straightened the barrette in her hair.

“But—” Diana began.

I told her not to ask anymore questions, hoping that we could move on immediately, but my sisters began to fidget. Katy picked at her collar and Leanne inched towards the grass.

I was losing them, I could feel it. We could become base so quickly. Curtesy and upbringing lost to a few uncertain moments. I felt the absence of adulthood, my small limbs incapable of rallying what was required. I tugged my sisters closer, believing that nearness would bring understanding, that the bond of skin and blood would commit us to a shared consciousness. I willed the magic of the rituals I performed late at night to flow through me. But in daylight there was no way to chant or contort, and any slight of hand would be seen. I saw nothing but expectation in their faces.

“Mother will want to know all about our day after school so we have to behave. We don’t want to disappoint her, do we?” I asked.

Leanne and Diana swung their heads back and forth.

“Definitely not,” Katy said.

I looked between the three of them, watching their green eyes for some sort of assurance. I found nothing to make me sure.

“Let’s go.”

_

My mother returned, but there was no party or hurricane. Nothing happened to signify such an incredible event. She was simply there when we came home from school on the third day. Her blonde hair hung limp and her lipstick was splotchy, as if her hands had been shaking when she applied it, but she was home. She opened the door and looked at us as if she was surprised to find us there. I wondered who she was expecting instead.

For weeks afterward I would jerk up in the middle of the night wondering if I’d heard something crack from another room. I thought with absolute certainty that her disappearance could only happen with a bang.

Hlengiwe Mkhwanazi

A native of KawZulu-Natal and former resident of Cape Town, South Africa, soprano Hlengiwe Mkhwanazi is a first-year member of the Ryan Opera Center. She obtained her diploma in opera in 2010 and her postgraduate diploma in music performance in 2012, both from the University of Cape Town, South African College of Music. In Vienna Mkhwanazi has participated in master classes with Fiorenza Cossotto and Giacomo Aragall. The soprano’s successes in competitions include her homeland’s SAMRO International Singing Scholarship (second prize) and Muzicanto Singing Competition (first prize), as well as Vienna’s 2012 Hans Gabor Belvedere International Singing Competition (second overall prize, media jury prize, audience prize).

Among her leading roles in Cape Town have been Fiordiligi/Così fan tutte, Konstanze/Die Entführung aus dem Serail, and Antonia/Les contes d’Hoffmann, all at Cape Town Opera; and both Stravinsky’s Anne Trulove/The Rake’s Progress and Rossini’s Madama Cortese/Il viaggio a Reims at Baxter Theatre. She has also been heard in the United States, portraying the role of Susanna/Le nozze di Figaro at Brown University. Hlengiwe is the winner of the Luminarts singing competition for women 2015. She made her debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago as Clara in Porgy and Bess 2014/2015 season. Hlengiwe will make her debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago as Barbarina in Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro 2015/2016.

Patrick Segura

Patrick Segura is a video, performance, and installation artist living in Chicago. Patrick received his BFA in Painting from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in 2011 and his MFA in Fiber and Material Studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2014.

Dealing with issues of body, play, virtuality, and sexuality, he draws from his background of gaming to create structures for understanding these ideas and their relationships. He embraces emergent technologies to helps excavate his conceptual territory. Patrick is the recipient of the College Art Association’s Professional Development Fellowship, SAIC’s Dean’s Scholarship and Grant, as well as the Clay Morrison Scholarship. He was also chosen to represent SAIC in EXPO Chicago. Patrick has shown work in Prospect 2, Acadiana Center for the Arts, and Sullivan Gallery. To learn more about Patrick visit Patricksegura.com

- Gardalku – Land of Rocks and Pillars (Virtual Reality)

- Land of Rocks and Pillars (Virtual Photography, two landscapes)

Lenard Simpson

Lenard Simpson is a Luminarts Fellow in Jazz. Saxophonist Lenard Simpson is a rising jazz musician from Milwaukee, WI. He was a member of the Batterman Ensemble at the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music, a group that was selected to participate in the Charles Mingus competition in New York in both 2012 and 2013. In 2012, Simpson won an Outstanding soloist award at the Charles Mingus competition and had the opportunity to play with the Charles Mingus Big Band.

In addition, Simpson was selected as 1 of only 32 high school students in the country to participate in the 2013 Grammy Camp Jazz Session, one of the most prestigious opportunities for high school musicians. Simpson has played with artist such as Brian lynch and Arturo Sandoval. Simpson is a junior at Northern Illinois University where he studies with Geof Bradfield. He has a driving passion for music and jazz and enjoys passing on his knowledge.

Sammi Skolmoski

Sammi Skolmoski is an art maker, writer, and Chicago native with professional experience in music journalism, radio broadcasting, print-making, bookbinding and floristry. My work involves vigorous exploration of obsessions and fascinations. If a thought shimmers, I pounce. Then I examine it under a microscope. Then I examine it from a safe distance, as the moon. Then I kick it, gently, around on the ground to see how it will react. This way of working relies on deftness in a multitude of media—whatever the piece should require, I do. I make.

I am currently pursuing an MFA in Writing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as a New Artist Society Scholar, a Smith Enrichment Scholar, and a Grace and Walter Smith grant recipient, and will be applying to receive a dual degree in Fiber and Material Studies this fall. In addition to poetry, I work with fiction, experimental and hybrid forms, sound, and visual media— including bookmaking, drawing, stitch, embroidery, et. al. But it all began in poetry, in getting lost in books. In 2009 I received my B.A. in Journalism and English as a University Provost Scholar and Knights of Dabrowski Scholar from San Diego State University. I have been published in San Diego Citybeat and San Diego Magazine and edited and founded several small-batch zines. In May of 2015, Patient Sounds (intl.) released a tape of my recorded poetry and sound collages as part of a limited edition Poesis series.

Sound + Vision, by Sammi Skolmoski

He hears those

lonely, gone mops,

Lennon shook hands, said

you, now,

so he does.

He hears those

streams pour through

though floorboard don’t

show a drop,

no taste.

He hears those

melodies slunk off bottlecap

jukebox slickster lips

gettin’ down,

three, four.

He hears those

bubble gum licks,

cringe, the sweet stuff

stuck on you,

babe, stuck.

He hears those

fists push air in

two streams aside, give

way to blue-

rimmed blue.

He hears those

you stay here,

now, we go gone,

don’t hitcha head

there, boy.

He hears those

boys say, turn, but

arm bent back,

no violin songs,

can’t jut.

He hears those

beasts flip wide

still under, but

yellin’ like

it’s day.

He hears those

spilt inks run

over her face, spell,

her, too, son,

her, t—

He hears those

sticks snuffed out,

picks ‘em anyway

like dan-dee-

lions, and puffs.

He hears those

mouths move, own words

creeping out through

stranger fits,

out with it.

He hears those

sun morphs from sea bottom,

kicks them habits like a

drum, boy,

she never went.

He hears those

bottle clangs upstairs

one more, not today

almost done a

year, now.

He hears those

damn tunes so loud

you can put a

quarter in him

(no change).

I see that

skin turn back

from green, flip

on, flush like

oxen steed.

He hears me

say, hot damn, that

George can groove,

he says, yeah, but,

I hear John.

Brett Slezak

Brett Slezak is a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer and received an MFA in Creative Nonfiction Writing from Columbia College Chicago. His writing has appeared in Defunct, Ghost Proposal, and The Pinch, among other literary journals. He is currently working on a memoir about his time living as a teacher in the Republic of Cape Verde. Brett lives and works in Chicago.

Girls, by Brett Slezak

There was a stoop down the street from my apartment where women and girls sat and braided each other’s hair. It looked painful, ripping a comb through dark hair, but even the youngest of girls stayed silent during these styling sessions. Their expressions serene, their eyes looking past the dusty street that sat before them. Sometimes the women gossiped, sometimes they too were silent. Sometimes they called out to the boys that kicked a half-inflated soccer ball down the street, saying those things mothers say. Come back here. Don’t play so far away. Don’t play in the dirt after I just gave you a bath.

The girls changed their hair about once a week. A lattice of braids. A tightly knit ponytail. Dozens of small braids, falling like a spider’s legs. Big hair, full and fluffed, swooping like in black-and-white pictures of the old movie stars.

The girls who lived out in the country wore bandanas outside of school. They worked the fields, they fetched water, they woke up early and swept the house, they put breakfast on the table and a kettle of bathwater on the stove, they washed their families’ clothes, the towels, the bed sheets, everything, by hand. I saw them on the weekends, if I was traveling to the other side of the island, from the window of a crowded van. We would round a bend in Fajã and all of a sudden they would appear—buckets balanced on their heads, hands at their sides, precision and grace in their gaits. I would lean out the window and shout their names as the van zipped past—Janinne, Vanda, Vanézia—and I would see the warm flash of a smile and the fragmented movement of a hand shooting up into the air, some part of the word Mister or Teacher reaching my ears. I loved that fleeting moment of recognition, the moment in between when I called their names and when they found me with their eyes, when they were smiling because they had heard the sound of my voice and knew that it was me.

Often, after class, when the students had been dismissed and were free to play wildly in the courtyard—to buy flavored ice and lollipops and chewing gum, to heave bouncy balls off the concrete, to play soccer and dance to the American pop music that blared from the school’s loudspeakers—often, a few students lingered in my classroom and peppered me with questions. Abo gosta de São Nicolau, teacher? Merka é sab? Qual é mas sab: Merka o Cap Verd? I responded, Yes, I love it here. Yes, America is sab. It’s not that one is mas sab than the other, it’s just—they’re different. The girls, especially my younger students, the seventh graders, they asked if they could erase the board for me, they asked if they could carry the livro de ponto for me, they asked if they could carry my bag for me. They had been taught from a young age to serve, and to them service was a way of showing respect, it was a way of showing love. Toward the end of my two years in Cape Verde, when my hair was long, and I no longer missed those arbitrary things from my previous life in the U.S.—beer on tap, cheeseburgers, the ability to drive a car—the girls, having never before seen hair like mine, often asked if they could touch it. I always laughed and shook my head, I picked up my bag and told them that it was time to go, that everyone needed to be out of the classroom, and I shut the door behind me and walked down the stairs, through the courtyard, through the students dancing and shaking, through the students running and chasing and sliding, their flip-flops forever unable to find any traction on the dusty concrete, through the bouncy balls arching toward the sky, through the blaring music, Rihanna and Akon and Ke$ha, all of the songs that were popular in Cape Verde in 2010, through all of those afternoons, one piled on top of the other, so many that it seemed they would never end, that life would go on forever like that—dancing and skating, energized and electrified, the air charged, the day warm, the sky clear.

There were two bars that my roommate Nelson and I frequented in our neighborhood, and they were both named after the women who owned and ran them, Jacinta and Da Lapa. Jacinta’s doubled as the neighborhood’s grocery store, and it was not uncommon to stand at the cramped counter talking, drink in hand, as one of our students wandered into the store to buy a bag of rice. It took some getting used to, the idea that our students, especially those who lived in our neighborhood, had access into the private aspects of our lives—where we lived, where we hung out, where we drank. The Peace Corps had long been sending volunteers to teach in Ribeira Brava, and the volunteers that were ending their service as we began ours, those who had lived in the very apartment we now lived in, told us that there was no way around it—if you chose to drink in public, students would see you do it. But alcohol was a part of daily life in Cape Verde, and students never looked twice when they saw us with a drink in our hands.

Da Lapa was the mother of my student Jennifer, and her bar doubled as a restaurant. The bar sat in the front room of Da Lapa’s home. We learned from others that Da Lapa had a soft spot for Peace Corps Volunteers. She was a tough woman and she had to be—she ran a bar in a country where only men tended to drink in public, a country where alcoholism ran rampant. But underneath her stoic expressions there was someone who cared for us Americans. She smirked at our horrible Creole, she answered our questions about aspects of the culture we didn’t understand, she made us dinner long after she had said the kitchen was closed for the night. And we went out of our way to please her—we told her jokes and tried to make her laugh (it was always considered a success if she so much as cracked a smile), we offered to buy her drinks from her own bar, we always told her that the food was delicious. When we ate dinner there, we drank at the bar with men from the neighborhood, and we drank what they drank—grogue and póntche—and because the kitchen had been closed, the food often took over an hour to be prepared. By the time Da Lapa told us that the food was ready and led us back through the hanging beads and to her personal dining room, Nelson and I were often half-drunk. Dinner sat on the table in the corner—either beef or fish or goat and rice and French fries—and Jennifer sat in the center of the room, next to the table, totally wrapped up in the Brazilian novelas that played on TV at night. I had Jennifer in class during both the years that I lived in Cape Verde, first in eighth grade and again in ninth grade. We watched the TV with her as we ate and asked her questions in English, in an effort to have her practice what she was learning in school. She was one of the rare students who liked to practice English outside of the classroom. She didn’t worry about making mistakes or sounding foolish, she used the language unabashedly, to the best of her ability.

Sometimes, I’d walk into Da Lapa’s with Nelson or one of the other five volunteers who lived on the island, and Da Lapa would be out running some errand, and Jennifer would be tending bar. It was during these moments that I could see that Jennifer was learning from her mother. She kept a straight face, she poured with a steady hand, she kept silent tallies of who was drinking what and how many they’d had. But I also saw that she was doing things that her mother didn’t, things that I imagined Da Lapa had told her were necessary to do when behind bar. She pretended not to listen to our conversations. She spoke only when spoken to. The other volunteers—those who didn’t live in Ribeira Brava like Nelson and me, those who lived up in the mountains or on the coast—they tried to make Jennifer laugh like we so often did with Da Lapa. But Jennifer rarely broke character. It was an exception to get her to laugh when she was behind bar, let alone make her smile. And it was Brendan who one day asked her, Why the straight face? And she responded, Girls can laugh only Saturday, between noon and afternoon. If not, they’ll be considered liviana. We all laughed, but Jennifer didn’t. She turned her attention back to the TV in the bar. Wait, really? Brendan asked. Jennifer nodded a slow yes, and she kept her eyes trained on the TV in the corner. We asked her to explain to the word liviana. What did it mean? From what she explained it seemed to mean silly. Was she saying that if a girl laughed too much, she wouldn’t be taken seriously by men? That she’d be seen as easy?

But it wasn’t just Jennifer who expressed this idea. Once, when I was visiting with a family who lived a ten-minute car ride outside of Ribeira Brava, the mother of the house explained to me that her daughter laughed too much. I responded by saying that laughter was a good thing. It was something to be cherished. I was reminded of my younger sister Alana. She exuded joy. When we were younger, she became famous at our family dinners for her fits of laughter, laughing and snorting and squeaking, sometimes until she fell out of her chair. No, I said, laughter is a good thing. But the mother reiterated the same points Jennifer had made. Too much laughter meant a girl wouldn’t be taken seriously by men. I asked her to explain more, I said I didn’t understand. But she simply repeated herself. Too much laughter was not becoming on a girl. Her daughter needed to laugh less, otherwise there were going to be problems ahead. What was the problem with laughter? If a girl was not taken seriously, did it mean that no one would want to marry her? That couldn’t be the problem. From what I saw, Cape Verdeans rarely married. Sometimes women moved in with men, but it was an oddity for it to be under the covenant of marriage. There was a saying for a woman moving in with a man in the culture. Tra de casa. To take from home. The saying stemmed from years ago, when a man could show up at the house of a woman he wanted and throw her over his shoulder and take her kicking and screaming to live with him. Tra de casa. Could the problem be that if a girl laughed too much that no man would want that girl to move in with him? That she would never be taken from home? Possibly. Or was it that she’d be seen as a slut? Just as a girl to have sex with and then toss aside?

I was a foreigner in Cape Verde, and this meant that I only saw the surface of things, my eyes skidded along the shimmering surface of the ocean and I was dazzled by the colors, turquoise and blue, and by the beauty, waves crashing into rocks, water reaching up toward the heavens, but I wondered constantly about what lied beneath. Surely, there were things I couldn’t and didn’t see. Nelson and I went for hikes on the weekends, and often, alone in the middle of a deserted landscape, rocks and weeds and dust and sun, we came across abandoned items. A blown out shoe. A rusty can. A pair of torn girl’s underwear. The head of a doll, one eye missing. Wires and electronics, the inner workings of a computer. I wondered how these things came to rest and decompose there. Whose sandal gave way on this mountain? Who mutilated a doll in this cornfield? Who was drinking beer in this dried up creek bed?

I heard whisperings and rumors, things volunteers suspected to be true: Teachers were sleeping with students. But I had no reason to believe these things, I had seen no proof. I played soccer three days a week with the other teachers from school, we sometimes got a drink at the bar afterwards, and from what I observed, most of them took their work seriously. They were good people. But one day a teacher and I were walking up to our respective apartments, talking about the day’s game, and I was in the midst of saying something, retelling some story of a goal I had or hadn’t scored, how I knew where it was destined for in the moment I kicked it, that I could feel it on my foot, when one of my students passed us on the street, and he stopped listening to what I was saying, he hissed at her and reached for her hand, and she looked up and smiled, their fingers touched, their eyes made contact, and I stopped talking, and he didn’t notice. Something twisted in my stomach, everything flashed in and out of focus. I knew. Of course teachers were fucking students. Things happened behind closed doors and in cornfields and behind curtains pulled shut. I thought back to all of the torn underwear that I had seen on our hikes—how had I not made sense of it earlier? They weren’t discarded, they were left in haste. Two people had been working in the fields, they had been doing the chores my students did outside of school, she had been fetching water and he had been on his way to feed livestock, and an opportunity presented itself that at least one of them, if not both, desired to take advantage of.

Teaching in Cape Verde was immensely different than teaching in the United States. I saw students everywhere—at dances in town, at soccer matches, even at the beach. And in this way I knew them much better than a teacher could ever know his students in the U.S. I was invited into some of their homes for meals, to meet their families, to see where and how they lived. And I was charmed by them. It was impossible not to be. They showed me respect outside of school, they made sure to come up to me at social events and greet me, they went out of their way to make sure I felt welcome in their country. They smiled often, they were quick to laugh—simply put: They were happy. And I’d be lying to you if I told you I wasn’t more charmed by the girls than the boys. The boys were charming in their own ways—some in their playfulness, some in their dedication to English, some in their quiet reserve—but I knew the workings of the young male mind, I knew from my own adolescent years the ways it fantasized and lusted, and because of this the boys never appeared as innocent to me as the girls. I saw the way they ogled the older girls who walked by our classrooms, I found the notes they passed in class. I did not, however, know the workings of the young adolescent female mind, and in this way the girls, especially the seventh graders, appeared to me as some of the most innocent creatures on earth. Obviously, this line of thought was flawed and heavily biased, but a few female volunteers said that they felt the opposite—they knew how cruel adolescent girls could be, and they saw the boys as sweet and innocent. Even if I recognized my thinking as biased, it was hard for me to see it in the moment, and when the girls sat before me in class, when I saw them walking down the street, I wished for the world to be good to them. I worried about them growing up in a country that was not kind to its women, a country that referred to being involved with a girl as conquering her, a country where it was a source of pride for men how many pikenas they had (enamorada was the word for girlfriend, pikena suggested a status less important), a country that referred to deflowering a virgin as ratxa papaya—ripping open a papaya.

But not all of the girls struck me as innocent. In my first year teaching in Cape Verde I taught eighth and ninth grade, and while the eighth graders were transitioning from children to adolescents, a few of my ninth grade girls tried to make it obvious to me that they were women. They lingered in the door to the classroom, striking poses similar to something out of a Britney Spears music video and asked me in hushed voices for permission to enter the classroom. They unbuttoned the tops to their uniforms to show cleavage and applied makeup in class. In those first months, I was often in the middle of teaching something like possessive adjectives and one of the girls would raise her hand and say, Mr. Slezak, I love you, or, Mr. Slezak, I am crazy for you. When they did this, the girls always batted their eyes and smiled brightly, and the class quickly turned into a circus, students hooting and hollering, clamoring for attention. In those moments I always felt like I was babysitting rather than teaching. I tried to ignore it at first. I was convinced that if I never acknowledged the inappropriate, it would disappear, but it continued to happen, each time embarrassing me more than the last. Who were these girls? And where on earth did they learn this behavior? I went to a comparatively tame suburban high school in Illinois, and certainly, the girls there were never raising their hands in class to make declarations of love. Eventually, I set down the rule that these were not the kinds of things to be said inside the classroom and that if anyone told me she was in love with me during class, she would be asked to leave the class for the day. That solved the problem inside the classroom, but these girls quickly learned to make their professions outside of it. Again, I chose to ignore them, but that usually just made them say whatever it was they were saying louder. So I learned to smile and say, I know. That usually confused them into silence. I also learned that by engaging them in conversation, by stopping and saying, Vanessa, how are you today? How’s school? How’s your family? they were taken off-guard and answered the questions honestly.

But, for the most part, the girls were well behaved in school. The boys were often the class clowns, they caused the major disturbances. And the higher the grade level in Cape Verde, the more girls there were in the class. Boys often dropped out before they graduated, for a number of reasons—to farm, to fish, to play soccer. If you were male, a larger world beckoned from outside the classroom—the ocean called, the fields sang, trabadja enchada, there was earth to be tilled, the fishing boats, their colors peeling from them like papier-mâché, ached to be taken out on the water. But if you were a girl, there was school. At home there were chores. And one day there was motherhood. If girls dropped out of school and worked, they did it as empregadas, maids. Sure, if they finished school, if they went to college on another island—on São Vicente or Santiago—or if they went to Brazil or Portugal, they could get degrees, maybe become teachers. But there was no college on São Nicolau, and many families could not afford to send their children away. Motherhood was seen as something to aspire to. It gave life a greater purpose, a higher meaning.

The first year I taught, one of my students dropped out of school during the first weeks of class. No notice, nothing. One day she simply was not in her seat as I took attendance. I asked the class if she was sick, and they responded, No, teacher. Gravida. I didn’t know the word yet. They saw the confusion on my face, they cupped their hands to their bellies, they cradled imaginary babies in their arms. Oh, I said, pregnant. I wasn’t naïve enough to think that this kind of thing didn’t happen in the U.S., that students didn’t get pregnant in eighth grade, but looking out at their faces I couldn’t help but be somewhat shocked. They looked like children.

There was a street corner, across from the school, next to where the vans lined up to take the students back to their villages—Fajã, Cachaço, Juncalinho, Lompelado—and men posted up there and hung out, waiting for the last bell to ring and school to let out for the day. When the bell did finally ring, the students flooded the cobblestone streets, a pulsating mass of uniforms, light green and white pin stripes, moss green pants. The boys ran ahead and played soccer on the outdoor handball court, they lingered and sat on the railings on the sides of the street, some of them headed immediately home. The girls traveled in packs, they bought candy from the vendors—dróps and schwinga and shupetas—the kinds of hard candy that didn’t melt in the tropics. The men had been drinking, there were multiple bars in close vicinity to the school, and they had come out to the street to look at all of the movimento, to flirt with girls, to hiss and catcall. In passing, on my walks up the hill to my apartment, I heard these men say things like: Why don’t you visit me sometime in my house? Although, these things made me mash my teeth together, I knew that there were larger cultural forces at play. I knew from talking with Amanda, my girlfriend and a volunteer at a secondary school of the southern island of Fogo, that this type of behavior was not exclusive to São Nicolau. In fact, things were worse at her school. Police officers sometimes showed up, not to regulate, but to visit their girlfriends—students as young as eighth and ninth grade. They kissed and made out on school property, while these men were on the job.

One of these afternoons I walked up the hill and ran into two male teachers that lived on my block. One of them, Silvinho, was with his pikena. The other, Antonio, asked me if the Peace Corps was a religious group. I told him that it was not. He looked confused and then asked me why I didn’t go after girls in Cape Verde. I told him that I was dating Amanda, and that she lived on Fogo. But the confusion did not wash from his face. I was used to this. Cape Verdeans, in general, did not believe that it was humanly possible to remain faithful in long-distance relationships. Whenever I explained that I had a girlfriend on Fogo, men and women alike would respond: And what about here? Brett, you’re a man. You have needs. So I told Antonio that Americans, in general, didn’t have more than one girlfriend. And if I were to go after women on São Nicolau, Amanda would break up with me.

Silvinho put his arm around his pikena and said, She’s one of three.

It was in these moments and immediately after that I worried about my female students. I saw their faces when I stood in front of class, and I hated to imagine that one of them might stand next to her boyfriend, after having washed his clothes and prepared his meals, as he put his arm around her and proudly proclaimed, She’s one of three. And just as much, I hated myself in these situations. I hated the way I stood there. I hated that I couldn’t even think to say, Come on. You don’t have to say that. When it came to confrontation, when it came to standing up for what I believed in, I was never the man I wanted to be. I wanted to be someone to admire. But I always tended to be something of a coward, I watched the moments trickle by, I excused myself from the street, I said goodnight and went upstairs, to my apartment, where the door locked behind me, and I tried not to think about the things I didn’t say.

It was during one of Amanda’s visits to São Nicolau that we walked into Da Lapa’s to get a drink, and the bar was empty, and Jennifer was behind the counter. Amanda and I had been to the market in town, and we had fresh vegetables with us—green peppers, onions, tomatoes—and we had plans to make dinner together. We stood at the bar and each ordered Super Bock from Jennifer. And we got so immersed in conversation with her that we forgot about dinner and stood there, ordering beer after beer. The radio that sat on top of the refrigerator was on, and it was playing Brazilian hits, and Jennifer was talking about the music, about the meaning of the lyrics. She asked Amanda about Fogo. What was the island like? How was it different? Amanda asked Jennifer about her life on São Nicolau, and Jennifer joked about school and English class. The conversation continued on and on, about anything and everything—the size of the dogs on São Nicolau compared to the dogs on Fogo, the novelas that played on the TV, the places we hailed from in America—Chicago and Texas. It was one of those magical moments. I was dizzy from the music and the beer and from having Amanda at my side, and I could see that Jennifer was delighted to have Amanda present in the bar. The Peace Corps had long since sent female volunteers to Ribeira Brava, and it was possible that Jennifer had never before seen a woman in a bar drinking beer. But I could tell that Jennifer was more moved by having someone of the same sex, an American role model, taking interest in her life. When Amanda and I left to walk back to my apartment, when we started up the big hill, the sun was dipping behind the mountains to the west, and the sky was purple and dimming, our shadows elongated and fading.

Inside of the classroom Jennifer was fierce. I started each class period with oral questions, and she wanted to be called on for every answer. She waved her hand in the air, her lips pursed, her face taut with determination. She often got angry with me for not calling on her and sulked with her face buried in her arms; she felt that I did not call on her enough. Although Jennifer spoke English very well, she was not a very good test taker. And because the Cape Verdean education system was based around taking tests—each class had two tests per trimester that made up 80% of the trimester’s grade—she struggled to do well in school. She never made the Quadro de Excelência, a list reserved for the students with the top GPAs in the school. I had a handful of students who made the Quadro de Excelência every grading period. And one of my students who was always at the top of this list, one of the students who had some of the highest marks in the school, was Francelina.

Like Jennifer, I taught Francelina for two years, although the two of them were never in the same class. Francelina was in my most feared class—a collection of students who had failed previous years, some of them were as old as seventeen and still in eighth grade. They threw spitballs, they hit each other and spouted verbal abuse, they interrupted at every opportunity. I didn’t like to turn my back on them, I was often scared to write on the board. Francelina sat in the front row my first year, and she was one of a handful of students in the larger body of thirty who took the class seriously. She was shy and wasn’t as eager to participate in orally practicing the language as the other students. During in-class writings and exercises, she would call me over, asking me questions about the finer details of the lessons we had been learning in class. I knew from her writing that she lived in Aguas das Pratas, a small village in the mountains about an hour hike from the school in Ribeira Brava. I knew that her family was religious. They went to church on Sundays. I also knew from her written feedback that she loved the class, but that she wished the other students would behave. She wanted me to kick the troublemakers out of the classroom more often.

In ninth grade, she sat in the back right corner of the classroom. She participated more, she asked me more and more questions about the language. At some point, maybe when we were working on the future tense, she let me know that she wanted to be an English teacher when she was older. I was moved by this and told her that it was possible, that she was a great student of English. She, as with all of the other students I taught for two straight years, about eighty students in total, changed before my eyes. She grew from a small, meek eighth grader into a quiet, graceful young woman. She, like Jennifer when Jennifer was behind bar, tended to leave her face void of any emotion. But I also remember her laughing a lot more in ninth grade, her wide smile, her eyes the color of coffee.

After I left Cape Verde, when my two years in the Peace Corps were up and I returned to America, Francelina was one of my students who crossed my mind often. I wanted the best for all of my students, especially for the girls, especially for Jennifer, especially for Francelina. I wanted them to find love, to find partners who treated them right, to go to college and see the world, I wanted them to have meaningful careers, to be blessed with love and their lives gifted with joy. For me, Francelina represented the girls of Cape Verde—intelligent, hard working, poised, full of promise, graceful and waiting. The girls of Cape Verde, all of them, waiting—but for what? Waiting to set the table, waiting for the water to boil, waiting behind the bar, waiting for the men to get drunk and spill their drinks so they can kneel down and wipe the floor, waiting with the same blank expression on their faces, waiting for love, waiting for someone to come and whisk them away, waiting for an opportunity, waiting to have a baby, waiting for the spark to ignite the fire of their revolution, waiting and waiting, waiting for life to pass, waiting for death, waiting for the waiting to end.

One weekend during my second year in Ribeira Brava, we were having a party on the roof of our apartment for Nelson’s birthday and most of the neighborhood was there—friends, coworkers, off-duty cops, even the neighbors we didn’t really like. I had been drinking beer and póntche, and I was drunk. I had comedown from the roof to grab something from the apartment when Steve, a volunteer who was new to the island, found me. There’s a girl laying at the bottom of the stairs. Something happened. There’s a guy milling around.

I left the apartment and found Bia on her back at the base of the stairs, mumbling like she was sleep talking. One of my neighborhood friends, a guy with light brown dreads who everyone called Penalty, suggested we move her outside. Bia was a recent graduate from the high school and the pikena of Zezito, a strong, muscle-clad neighbor who lived in the apartment below us and worked as a guard at the island’s jail. I had seen her often outside on the street washing his clothes by hand, joking with the other women who lived nearby. Outside, Zezito was pacing around with worry, his hands on his head. People were trying to calm him down. They told him to leave, to go into his apartment, to call it a night. Bia started kicking in her sleep, I thought she was having a seizure. Penalty said, Her face. What happened to her face? I looked at her face, saw that it was bruised around the mouth, her eyes closed, kicking and mumbling like she was trying to fight herself awake, her hair done for the party, down and straightened, not the normal braids or in a ponytail, she wore it as my students wore it for special occasions. Her face. What happened to her face? She wasn’t drunk. She hadn’t fallen down the stairs. She was unconscious and dreaming. I heard snatches of conversation—the two of them had been arguing, she had found Zezito dancing with or kissing another woman, she had thrown something at him, called him names, he snapped, he punched her in the jaw, and she was out. People started leaving the party, filing out of the doorway, our friends, neighbors, the police officers, everyone looking the other way, everyone going home.

Nelson, I’m sorry, Zezito said later. I didn’t mean to ruin your party.

I’m not the one you should be apologizing to, Nelson told him.

Nelson and I talked about it that night and the next morning. We called our Peace Corps superior, told him what had happened, that we wanted to find the girl, we knew where she worked in town, we would ask her how she was doing, say that we would support her if she wanted to go to the police, that we’d be more than willing to file police reports. We were told not to get involved, that we had no idea how this thing was going to play out, that we needed to keep our distance from the situation. We should not find her at work. We should not go to the police. We should just stay away.

We were upset by what our superior had told us. Nelson and I talked about what we would do if this kind of thing had happened in the U.S. Our neighbor Elton, our best Cape Verdean friend, was over. If this had been our apartment in America, I would have called the police, I said. He would have been arrested.

Yeah, Elton said. In America.

I was conflicted but compliant. There had been officers at the party, what good would going to the police do? I wasn’t naïve enough to think that there wasn’t domestic abuse in America, that this kind of thing didn’t happen there, and eventually, upon returning home, I would witness a drunk couple running their car off the road, the woman getting out to storm away, the man following her and grabbing her by the arm, punching her in the face, telling her to get back into the car. Violence, when it erupts, is sudden, unexpected, without warnings or harbingers. I’ve learned that I don’t speak up in the face of it, I watch from a distance, I think of things I should do, and I slink away.

Zezito left the island for a couple of weeks. When he came back he said he had left to clear his head, that he had to get away because of the thing. I saw his girlfriend before I ever saw him. One day, about a week after the party, I left the house and saw that she was talking on the street with neighbors. Buckets of soapy water at her feet. Even though Zezito was out of town, she had returned to wash his clothes.

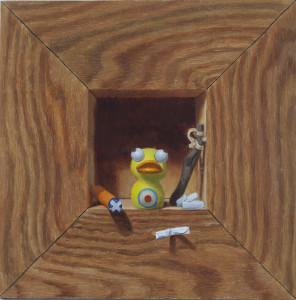

Kyle Surges

Kyle Surges is a Chicago based still life artist with a bachelors’ degree from the American Academy of Art. His medium of choice is oil paint. Like many of the great artists before him, Kyle has recognized oil paint as the superior medium for his approach to painting. It’s slow drying time and smooth texture allows for excellent control with a fine sable brush to create trompe l’oeil works of art. The term trompe l’oeil which is French for “deceive the eye,” is an art technique that uses realistic imagery to create the optical illusion that depicted objects exist in three dimensions. This type of art can also be considered photorealism or hyperrealism. Being a very time consuming technique, His paintings take anywhere from two to four months to complete.

In 2013 Kyle achieved gallery representation through McCormick Gallery in the West Loop of Chicago. He met the owner, Tom McCormick in a local juried art exhibition where he participated as a juror. In this group show, Kyle displayed a painting of a small, unwrapped miniature Hershey chocolate – Tom was immediately drawn to the piece and Kyle was awarded 2nd place in the exhibition and McCormick purchased the painting for his private collection. Later that year Kyle had his first professional solo show in October at McCormick Gallery. His next show with Tom will be in the Fall of 2016. Kyle has also exhibited work in numerous juried exhibitions; and been fortunate enough to win many awards. Kyle says his greatest achievement was becoming a Luminart’s Fellow in May 2015. “I was a finalist in the Luminart’s Visual Arts Competition for two consecutive years before winning the grant and Fellowship. It’s an award I’m truly humbled to receive.”

- Remembering Iwo Jima

- Walked in Lincoln’s Steps

Jung Tsai

A native of Taipei, Taiwan, violinist Jung Tsai started playing violin at the age of five and gave her first solo performance in National Concert Hall in Taipei in 1994. She has won 3rd prize in the Taiwan Chamber Orchestra Competition and was selected to give performances in the “Young Concert Artists Concert Series”. She made her debut playing Brahms Violin Concerto with Mannes Community Orchestra and New York Doctor Orchestra in 2011. In addition to solo performances, Ms. Tsai is also an intensive orchestral and chamber musician.

Ms. Tsai had joined the Civic Orchestra of Chicago and served as assistant concertmaster during the 2012-2013 season. In 2015, her string quartet was invited to Festival de Música de Santa Catarina in Brazil for the string quartet program under the guidance of Arianna String Quartet and has won the honorable mention in Plowman Chamber Music competition. In the past few years, she has attended several festivals including Schleswig-Holstein and Castleton Festival and had masterclasses with Mikhail Kopelman, James Buswell, Helmut Zehetmair, Josef Silverstein, Ivry Gitlis, Martin Beavor, Vadim Gluzman, Chee-Yun, and Gerardo Ribeiro.

Ms. Tsai received Bachelor of Music Performance at Mannes College where she studied with Prof. Nina Beilina and Masters Degree in Music Performance at DePaul School of Music with Prof. Ilya Kaler.

Thaddeus Tukes

Thaddeus Tukes is a skilled vibraphonist and pianist with more than 10 years’ experience and knowledge of multiple jazz, gospel, classical and pop arrangements. His highlights include performances at Carnegie Hall in New York and Chicago Symphony Orchestra Hall in Chicago.

Thaddeus earned top Jazz Vibraphonist in Illinois among high schools; A recipient of the Luminarts Jazz Fellowship, he studied with Ravinia Jazz Scholars; won the Kiewitt-Wang Scholarship from Jazz Institute of Chicago, worked five years as an apprentice with the Gallery 37/After School Matters Big Jazz Band, and was a winner of Fidelity FutureStage Young Artists competition during his years at Whitney Young Magnet High School.

Thaddeus has played at various Chicago locations, including the Chicago Jazz Festival, Fitzgerald’s, Ravinia, Room 43, Millennium Park, Jazz Showcase, Andy’s Jazz Club, and Buddy Guy’s Legends. He currently attends Northwestern University with a dual degree concentration in Jazz Studies and Journalism.

Jialiang Wu

Jialiang Wu has performed both solo and chamber recitals in major venues in China, North America, and Europe. After giving his debut in Shanghai concert hall when he was 14, he was featured in Chinese television, radio, and magazines. He has also won a number of prizes and scholarships including the Shanghai piano competition, Thaviu-Isaak Piano Competition at Northwestern University, both Mannes concerto competition and Northwestern concerto competition, semi-finalist in Tchaikovsky piano competition for youth musicians, New Orleans piano competition,

Schoenberg pianist scholarship, and the Esther Yochim Endowed Fellowship. Recent highlights in the United States include his debut at Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center with conductor JoAnn Falleta, showcase radio appearance on New York’s WQXR and the Dame Myra Hess Concert Series on Chicago’s WFMT. Jialiang has performed in music festivals including Shanghai international piano festival, Mannes music festival series, IKIF, Gilmore international keyboard festival and studied with world-renowned virtuosos including Yefim Bronfman, Richard Goode, Fu Ts’ong, Garrick Ohlsson, Lazar Berman, and Nicholai Lugansky.

Born in China, Jialiang attended the Shanghai Conservatory of Music as a student of Dachun You. He received both his Bachelor and Master of Music degrees from Mannes School of Music in New York, where he studied with Pavlina Dokovska . He is currently pursuing the Doctor of Music degree program with Alan Chow at Northwestern University.

2014 Fellows

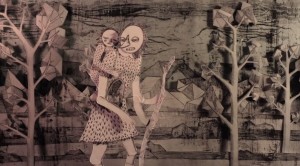

Ali Aschman

Ali Aschman is a visual artist working with experimental narratives through a number of media including animation, sculpture, installation, drawing and printmaking. She earned a BA from the University of Cape Town and an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is a Luminarts Visual Arts Fellow, a current HATCH Projects Artist Resident, and a post-graduate intern at the John David Mooney Foundation. Previous residencies include ACRE, the Rensing Center, the League Residency at Vyt and Elsewhere. Her animations have been screened in numerous international film festivals, and her work has been exhibited at Parlour, Flux Factory, Storefront Brooklyn and Norte Maar (New York), Space 1026 (Philadelphia), Whatiftheworld (Cape Town), Spudnik Press, Chicago Artists’ Coalition and the Hyde Park Art Center (Chicago), among others. A solo exhibition of her work is scheduled for January 2016 at Dittmar Memorial Gallery, Northwestern University in Evanston, IL. Ali lives and works in Chicago. To learn more about Ali check out her website at Aliaschman.com

- Elsewhere the Survivors

Emily Camras

Emily Camras is a Luminarts Fellow in Classical Music, cello, and one of the youngest recipients to be awarded the Fellowship. Emily won 2nd place in the 2012 Music Teaches’ National Association National Finals, and was a tied first place winner of the Walgreens Concerto Competition. Emily has appears as a soloist at the Chicago Cultural Center, Meadowmount School of Music, and the Young Steinway Concert Series in Skokie. He Chamber groups won recognition in the St. Paul and Fischoff Competitions.

In addition to winning the Luminarts Fellowship, Emily was awarded a fellowship in the 2014 National Repertory Orchestra in Breckenridge, Colorado. She also participated in the Texas Music Festival and the National Youth Orchestra of the United States as a fellow recipient, performing in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and the BBC Proms under Valery Gergiev. For four years she served as co-principal cello of the Midwest Young Artists in Highwood, Illinois. Emily began cello at age ten, and studied with Tanya Carey while attending the Illinois Math and Science Academy. Her former teachers include Andrea LaFranzo and Melissa Kraut. She currently studies with Richard Aaron at the University of Michigan, where she is pursuing a double major in cello and physics. She place to pursue a performance career while continuing her involvement with science, Judaism, and liberal arts.

Tracy Cantin

Tracy Cantin is a Luminarts Fellow in Classical Music, voice. Praised for her “international voice” that is “powerful, articulate, and modulated at will”, soprano Tracy Cantin is quickly becoming one of Canada’s top young artists. Having recently won the attention of American audiences, Tracy joined the ranks of the Lyric Opera of Chicago, as a studio ensemble member at the prestigious Patrick G. and Shirley W. Ryan Opera Center, for their 2012-13 season, 2013-14 season, and their 2014-15 season. This season, Tracy made her International concert debut where she was the soprano soloist alongside bass-baritone Bryn Terfel in two performances of Beethoven’s Symphony no.9 under the baton of Sir Andrew Davis with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. She also made her Ravinia Festival debut performing as the soprano soloist in the newly re-orchestrated World Premiere of Berstein’s Songfest, arranged for chamber ensemble and conducted by Alexander Platt.

Tracy made her American debut in Chicago, singing Countess Almaviva in Le Nozze di Figaro, and Mimì in La Bohème with the Civic Orchestra at the Chicago Symphony Center. She made her professional operatic debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago, singing the Fifth Maid in Strauss’ Elektra, in the highly acclaimed production by Sir David McVicar, conducted by Sir Andrew Davis, where she was praised in Opera Today for her “admirable attention to diction”. Most recently, Tracy has been heard on stage at the Lyric Opera of Chicago as Countess Ceprano in Verdi’s Rigoletto, as Fiordiligi in Mozart’s Così fan Tutte, and as the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier with the Grant Park Music Festival. Tracy is a graduate of McGill’s Schulich School of Music, where she was enrolled in their coveted Artist Diploma program in Voice Performance, under the tutelage of American Baritone Sanford Sylvan. With Opera McGill, she debuted with the role of Mimì in Puccini’s La Bohème, and went on to sing the roles of the Governess in Britten’s Turn of the Screw, and Donna Anna in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. She was also the featured soprano in an evening of scenes from Verdi’s most beloved operas, in which she performed the final acts from Otello (Desdemona) and La Traviata (Violetta). Other operatic credits include Alice Ford in Verdi’s Falstaff (Opera NUOVA, Highlands Opera) the Mother in Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel, (University of Alberta Opera Workshop) and Nella in Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi (Opera NUOVA).

Equally at home on the concert stage, Tracy was recently engaged as the soprano soloist with l’Ensemble Sinfonia de Montreal and the Illinois Philharmonic Orchestra in Beethoven’s Symphony no. 9. She has also been heard as a Soprano Soloist in Bach’s Magnificat, Vivaldi’s Gloria, Handel’s Messiah, and Mahler’s Symphony No.2. An advocate of Art Song literature, Tracy recently performed recitals in London and Montreal, which featured such masterpieces as Strauss’ Vier Letzte Lieder, Barber’s Despite and Still, Britten’s Les Illuminations, and Debussy’s Proses Lyriques. Tracy has been the grateful recipient of many scholarships and awards over the years, and was recently the winner of the prestigious Lois Marshall Memorial Competition, as well as the St. Andrews International Aria Competition. She is currently supported by the generous donations of Mrs. C. G. Pinnell, the Jacqueline Desmarais Foundation, and the Edmonton Community Foundation. Tracy holds a Bachelor of Music in Voice Performance from the University of Alberta, and a Master of Music in Voice Performance and Literature from the University of Western Ontario.

Sun Chang